In 2012, legendary poker player Phil Ivey and his trusted playing partner Cheung Yin Sun catapulted edge sorting into the public domain when the media got word of them using it at Crockfords Casino in London. Within two years, in 2014, Ivey's unsuccessful lawsuit to recoup his $12 million in winnings from Crockfords garnered international attention. It didn't take long before Ivey was sued by the Borgota casino for $9M.

Why all the hoopla? As it turns out, Phil Ivey extensively used edge sorting with Cheung Yin Sun at the Borgata Casino. That's where the duo won $9 million using this card-playing technique. At the time of writing, the case was still ongoing. By 2 June 2015, Sun lost her lawsuit to recover $1.1 million in confiscated winnings from Foxwoods Casino back in 2011. What was the verdict? The jury decided she was guilty of using edge sorting to win the money.

Edge sorting isn't the flavour of the day in courts nowadays. More specifically, Phil Ivey and Cheung Yin Sun have a rough time vis-a-vis edge sorting in the courts. I know of cases where edge sorting hasn't been prosecuted in civil courts. The APs (advantage players) kept their winnings without litigation being levelled against them. One of these stories is presented in greater detail below. The problem is the money – the bigger the amounts, especially in millions, the more serious the casinos take this matter.

If you're interested in reading more about this topic and how Phil Ivey successfully (or unsuccessfully) employed it, take a look at these articles:

- Phil Ivey -v- Crockfords

- Podcast on Bluff.com about Phil Ivey

- Phil Ivey and Yellow Journalism

- Beating the House: From Affleck to Ivey

In the story below, I detail an authentic experience with edge sorting. As a consultant on this topic, I was surprised to learn that it was none other than Cheung Yin Sun's team.

I wrote this post for you in 2012, and about three years ago (2009), I was busy playing double-deck blackjack at a large casino just off the Las Vegas strip. Admittedly, I was counting cards. In fairness, I was waiting to have dinner with somebody and decided to play blackjack. My card counting abilities are pretty well-tuned, and I played for low stakes anyway. I wasn't going to sound the alarm on the radar, especially not with $5 minimum and $40 maximum bets. The casino didn't perceive me to be a threat whatsoever. My hourly pay for this activity ranged between $8 and $10 on a good day.

After so many years of playing blackjack professionally, I was taken aback when I was tapped on the shoulder. As it turned around, a nattily-clad individual introduced himself to me. He was the table games shift manager. He proclaimed, 'Dr. Jacobson, we know who you are. What are you doing?' What an odd question, I thought. Clearly, the man felt somewhat embarrassed to be asking these questions. But he wasn't the only one – I was beside myself. I stood up and moved away from the table.

The gentleman and I made small talk and cleared the air somewhat. Then, we focused on more critical issues as we discussed security-related concerns. I asked him if anything was going on at the casino that he wanted me to look into for them. I wondered if there were any security issues that his team couldn't figure out. I was happy to provide my opinion on these types of matters. But what happened next was even more startling. The casino shift manager told me something that caught me unawares – a card marking team had been successfully operating for several months at the casino.

The shift manager explained, 'They seem to know what the cards are when they play.' But it was the following statement that completely baffled me. He explained that after carefully examining the decks of cards, the casino found no indication that they were marked. So, it appeared as if the team was doing nothing wrong and everything right, but he was sure that this team was marking the cards, despite no marks appearing. How could something like this be possible when there was no evidence of such?

My Examination Begins in Earnest

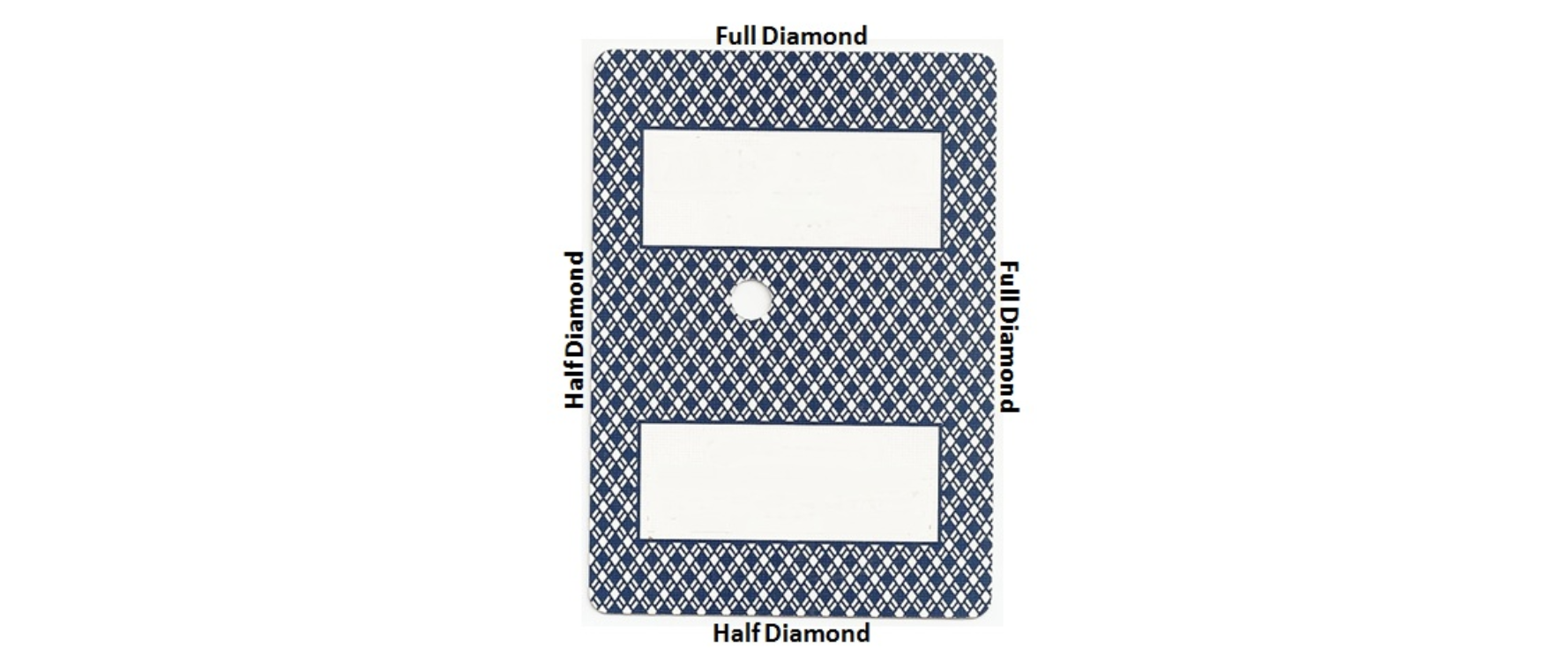

Here's what I did: I asked the shift manager to present me with a deck of cards. I walked with them to a table in a closed pit. He retrieved a fresh deck of cards from the back. The card seen below is an example of one used by another casino in Las Vegas. But, it's similar enough to the one that I saw. What's particularly striking about this card is its asymmetry – it looks different because of the way the patterns are printed on the card. Look carefully, and you'll see that the two adjacent edges of the playing cards have a blue half-diamond shape, but the other two edges have a blue full diamond-shaped. That's a significant difference. I must tell you that all the cards in every deck had this feature on them.

So, if you look at the top of the cards, you will notice a full diamond, and if you look at the bottom, you will see a half diamond. This asymmetry means that an edge-sorting team of players can rotate the cards. When players collaborate or, more appropriately, conspire to defeat the casino, they turn the cards to help one another read the values before they are dealt. Only the essential cards are rotated so that the full diamond shape is displayed at the top and right edges of the cards. Players turn the other cards to show the full diamonds on the bottom and left edges. An example will help to clarify this. In blackjack, you can rotate 10-value cards and Aces in one direction, but all other cards are rotated in another direction.

This makes it possible for edge sorters to 'read' the dealer's cards. Naturally, cards are shuffled around, but the edge sorting team performs their actions during every hand played. After multiple shuffles, most of the cards are sorted. Unfortunately for the casino, their biggest fault is sticking to a strict card shuffling and dealing regimen. This works against them. I relayed this information to the shift manager. I told him that an easy fix for this is to have a turn in your shuffle. 'You do have a turn, don't you?' I asked him. His face went white. He admitted that there was no turn in the shuffle. They were too busy watching how the team was marking cards, but the cards were pre-marked and had nothing to do with what the team was doing.

Effectively, the team used the casino's equipment, rules and procedures against them. After several minutes of absorbing everything I was telling him, my newfound friend – not – said that he would get back to me and gave me his business card. I never heard from the fellow again, but I expected that. Now, please understand me. Casinos that use these playing cards aren't making mistakes in their product choice. These types of cards are widely used. My collection of cards from some four dozen decks from a multitude of casinos has approximately 67% of them that can be edge-sorted. So, the solution isn't as hard as it seems. It's a trivial fix. Every single shuffle should include a turn – that's it. Whether it's a shoe, a single deck, or a double deck doesn't matter.

Let's say you are using an automatic card shuffling machine. In this case, a manual turn of the cards is all it takes to remedy edge sorting problems. The equipment itself is functional. There's nothing wrong with it. After every round of play, all it takes is a manual turn of the cards. Recently, I frequented a casino that had edge sorting problems. I watched the blackjack shuffle, and lo and behold; there was a turn. I asked the pit supervisor why they employed a turn. His answer was bang on the money: So, the cards can't be identified by some pattern on their backs. Next, I walked over to the novelty games. They use automatic card machines. I watched, and the casino didn't use turns. It is evident that management knew that a turn was critical, but the casino didn't implement it here. Novelty games tend to take security and protection less seriously – a no-no.

There's a lesson to be learned here. You can't take anything for granted while protecting casino games from savvy players. Often, there is an easy fix to problems. But you need to identify the problem and know what the fixes are. Otherwise, you could spend months, possibly years, wondering what players are doing, how they're doing it, and come up empty-handed every time. Persistence isn't always the solution to these types of problems.